Herat: The Pearl of Khorasan | Shabnam Nasimi

"If any one ask thee which is the pleasantest of cities,

Thou mayest answer him aright that it is Herāt.

For the world is like the sea, and the province of Khurāsān like a pearl-oyster therein,

The city of Herāt being as the pearl in the middle of the oyster.”

— Mawlana Rumi, 1207–1273 AD

In August 2014, I had the privilege of visiting Herat with my father—a city once described by the famed poet Rumi as ‘the Pearl of Khorasan.’ Keen to see more of Afghanistan beyond Kabul, we boarded an Ariana Airlines flight—a short, uneventful journey to Herat International Airport, known locally as Khwaja Abdullah Ansari Airport.

Our stay was with distant relatives in their elegant, traditional home, where hospitality came in the form of endless cups of black cardamom tea and trays of dried mulberries, roasted nuts, and sohan—a special Persian sweet, crisp and fragrant with saffron and cardamom.

Herati hospitality is generous, warm, and effortless, though I have to admit, their distinct Persian dialect often left me second-guessing whether I had truly understood what was just said. It was lyrical, familiar yet foreign.

Herat—or Aria, as the Greeks once called it—felt like a world apart from the Afghanistan I had known.

The city had an elegance to it and an old-world charm, even beneath layers of dust and neglect. Its ancient architecture, paved streets, and once-grand boulevards told a different story, one of a city that had known power, refinement, and prestige.

The people, too, seemed shaped by this history—a mix of modern Afghanistan and echoes of Iran, their mannerisms and accents carrying traces of centuries-old ties.

Relying on Sahar, the youngest daughter of our hosts, as my guide, I walked Herat freely. Just the two of us, navigating the city as though it were a living museum.

We visited the Great Mosque of Herat, built on the site of two Zoroastrian fire temples. We stood before the mausoleum of Queen Gawharshad, the visionary queen who transformed Herat into a centre of art and knowledge. We saw the Citadel of Herat, which has withstood the test of time for over 2,500 years. At Gazar Gah, we stopped at the tomb of Khwajah Abdullah Ansari, the Sufi poet and philosopher. I remember standing at his tomb for a long time, thinking about how words can outlive the people who wrote them.

And I found myself captivated by a city that had once been home to a cultural renaissance—one that rivalled Florence long before Europe had its awakening. Caught in the spell of a place hiding in plain sight—overlooked, underappreciated. Like a rare manuscript on Afghanistan I once stumbled upon at Foster’s Bookshop in Chiswick, left to gather dust on a neglected shelf, Herat waits—its stories, its history, its grandeur—all there, for those willing to listen.

So, pull up a chair, pour yourself a cup of tea, and let me tell you about Herat.

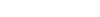

Beautifully rendered map of Herat. London : James Wyld, 1880.

Situated along the banks of the Hari Rūd River, bordered by Badghis and Ghor provinces to the east and Sistan to the south, lies a city as old as the wine it once produced—Herat. A place where history has been written and rewritten for over 5,000 years.

Herat’s origins stretch deep into antiquity, long before the rise of the Achaemenid Empire. It was known as Haraiva in Zoroastrian Avesta (1500–500 BC), named after the river that nourished its land—the Hari Rūd, meaning "abundant in water" in Old Persian.

Its significance is captured in the rock-cut reliefs at the royal Achaemenid tombs of Naqš-e Rostam and Persepolis in Iran, where envoys from Herat are depicted bringing tribute to the Persian kings. Dressed in Scythian-style attire, they wear tunics and trousers tucked into high boots, with twisted turbans wrapped around their heads. These reliefs offer a glimpse of Herat’s place within the vast Achaemenid world—an important province contributing military forces, agricultural wealth, and highly prized horses to the empire.

Even Herodotus, the Greek historian, recorded Herat’s inclusion in Xerxes' army against Greece in 480 BC.

By the time Alexander the Great marched into these lands, the city they would call ‘Aria’ was already a city of influence. It was ruled by Satibarzanes, one of three key Persian satraps of the East, alongside Bessus of Bactria (Balkh) and Barsaentes of Arachosia (Kandahar). But beyond its politics and wars, Herat was thriving in another way—its fertile land, abundant orchards, and flourishing vineyards made it a city traditionally renowned for its wine.

In these early days, Herat would have had hundreds to thousands of hectares under vineyard cultivation, making it comparable to major European winemaking regions like Bordeaux, Tuscany, and La Rioja.

The city became renowned for its Fakhrī grapes, producing what was described as the finest wine. Persian poets often spoke of wine as a symbol of divine ecstasy, and it seems fitting that a city famed for its spiritual elixirs would go on to inspire centuries of poetry, philosophy, and art. Persia is considered one of the oldest winemaking regions in the world—so who can say that Herat was not among its pioneers?

Even Herat’s winds were believed to hold healing properties, inspiring an old Arabic saying:

"If the soil of Isfahan, and the north wind of Herat, and the water of Khwarazm were but all found in one country, verily but few people would ever die there."

When Arab armies arrived in Khorasan in the 650’s AD, Herat was counted among the twelve capital towns of the Sasanian Empire. It was home to a Christian community, and a bishop from the Church of the East lived there.

And so, Herat resisted hard—with a fierce pride for its heritage and history. Hephthalites of Herat fought against the Arabs at the Battle of Kohestān, attempting to block their advance on Nishapur. Though defeated, they continued their resistance for decades, fighting well into 671–72 AD.

By the medieval period, Herat had become a city of commerce and culture, its bazaars buzzing with merchants, scholars, and travellers. Under Sultan Maḥmud of Ghazni, who gained control of Khorāsān in 998 AD, Herat became one of the six Ghaznavid mints, home to 12,000 shops, 6,000 bathhouses, 359 colleges, caravanserais, dervish convents, fire temples, and nearly half a million homes.

I actually had the chance to visit a caravanserai in Herat, and it was incredible to see a piece of history come alive. I was told that caravanserais were the lifeblood of trade along the Silk Road—more than just roadside inns, they were spots where merchants could rest, store their goods, and share stories from faraway lands. Herat, once a key stop on this ancient trade route, had at least five caravanserais, though now only three remain, their walls slowly crumbling from years of neglect. In places like Iran and Uzbekistan, many of these historical buildings have been carefully restored into hotels and cultural landmarks, but in Afghanistan, after decades of war, they’ve been left to decay. In their heyday, caravanserais were meeting points for traders, scholars, and travellers, where goods, ideas, and even religions were exchanged.

Yet its wealth and prestige could not protect it from devastation.

The Mongols laid siege to Herat twice. The second siege in 1222 AD was followed by a massacre so brutal that one account claims 1.6 million people were beheaded, leaving "no head on a body, nor body with a head." But even this unimaginable destruction could not erase Herat. It would rise again.

A century before the European Renaissance began in Florence, Herat had already led its own—a golden age of art, literature, and learning, setting the stage for an artistic legacy that would shape the Mughal courts of India and beyond.

It was under the Timurid dynasty in the late 14th century that Herat reached its greatest heights. King Shah Rukh, son of Tamerlane, became governor of Herat and transformed it into a centre of knowledge and art. The city’s golden age peaked under Sultan Husayn Bayqara (1469–1506 AD), whose prime minister, Mir Ali-Shir Nava'i, was both a renowned poet and a great patron of architecture. During this period, Herat’s religious and educational institutions grew in influence, its bazaar filled with traders, and royal patronage supported a growing culture of manufacturing and trade.

But it is impossible to speak of Herat’s history without mentioning Queen Gawharshad Begum, Shah Rukh’s wife and one of the most powerful female patrons in Persian history.

She turned Herat into a cultural and artistic powerhouse, with a focus on Persian miniature painting, literature, and architecture, commissioning the Musalla Complex, with towering minarets and splendid mosques said to rival those of Samarkand and Isfahan. Many of Herat’s most breathtaking palaces, madrassas, and gardens date from this time.

A champion of education, culture, and art, Gawharshad advised her husband in governance and diplomacy and accompanied him on state affairs, showing us that her influence extended far beyond architecture. She was a strategist, ensuring Herat’s political and cultural dominance in a world where empires rose and fell overnight.

Even after her husband's death, she navigated the turbulent Timurid court with remarkable resilience, securing power for her son and continuing her patronage of learning, encouraging girls to study.

Nearby, in the village of Gazar Gah, the shrine of the Sufi saint and poet Khwājah Abdullāh Ansārī (1088 AD)—known as Pīr-i-Harī (the Old Man of Herat)—was rebuilt around 1425 AD, cementing the city’s role as a spiritual centre.

Even as dynasties changed, Herat remained crucial.

The Persian king, Shah Abbas the Great, was born in Herat, and Safavid texts referred to it as "the greatest of the cities of Persia."

During these centuries, Herat nurtured extraordinary minds. Jami (1414 - 1492 AD), the Sufi mystic, poet, and scholar, wrote his Haft Awrang ("Seven Thrones"), a masterpiece of Persian literature, combining together spiritual allegories, love stories, and moral reflections. His illustrated manuscript, decorated with gold leaf, eventually found its way to the Mughal Empire in India, where it remains preserved in Washington, D.C.’s Smithsonian Institution.

But the most towering figure of Herat was Kamal al-Din Behzad (1450–1535 AD), the father of Persian miniature painting. His work didn’t just capture the grandeur of Persian court life—it defined it. His brush brought to life the world of sultans and poets, gardens and battlefields, lovers and mystics, each figure meticulously detailed. His influence stretched far beyond his own time, shaping the Mughal ateliers of India and earning him the role of director of the royal atelier in Tabriz, where he trained the next generation of artists.

It was here, in Heat, that Persian miniature painting reached its peak, where art was not just decoration but a language of its own. And so, it feels only right to dedicate a separate story just to him—to how Behzad turned Herat into the birthplace of Persian miniature painting.

Herat has been tested by war and conflict, yet continued to rise like the mythical Persian Simurgh.

Walking through the city feels like running your fingers over the pages of an old manuscript—its corners frayed, its ink smudged, but its story still intact. The minarets lean a little now, their tiles missing in places. The grand gardens, once filled with poets and philosophers, now silent and abandoned. The great caravanserais which hummed with merchants and travellers now stand quiet, decaying.

Jami once wrote:

"The price of a man consists not in silver and gold,

The value of a man is his power and virtue.”

So as you’ve seen, Herat was never just about power or riches. It was a place where knowledge, art, and wisdom were valued above all else. A city that shaped ideas, nurtured poets, and left behind a legacy greater than stone. It is still here, waiting to be remembered—not in ruins, but in words, in ideas, in the stories it left behind.

-

Shabnam Nasimi is the co-founder of FAWN (Friends of Afghan Women Network). She served as a senior policy advisor to the UK Minister for Refugees and Minister for Afghan Resettlement. She is a writer, commentator and a human rights advocate.