The Story

kamra-e-faoree

Since the early 1950s street photographers and studio portraitists in Afghanistan have been using the basic photographic process Henry Fox Talbot introduced to England in the 1840s: a big, box-shaped wooden camera and dark room in one, known as the kamra-e-faoree. Their trade survived the Soviet invasion of 1979, the civil war that followed it, Taliban rule in the 1990s and the invasion by America and the allies in 2001. Now, though, the rise of digital technology in Afghanistan kamra-e-faoree is almost over. See more here.

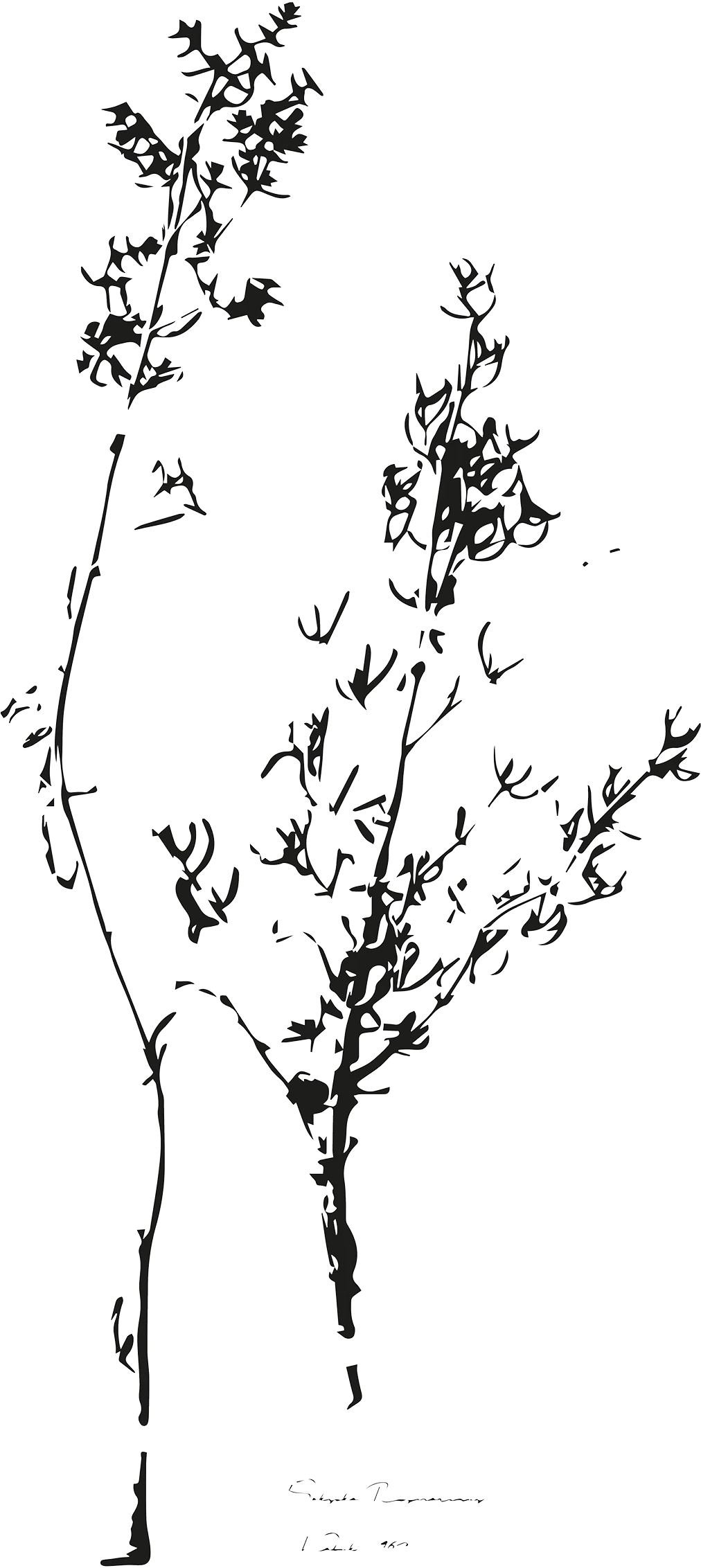

Before the box camera, a small number of photographers catered only to the rich and privileged. This humble apparatus democratised photography, allowing ordinary citizens to have their portraits taken relatively cheaply. The boxes were made by local carpenters – only the foreign-produced lens had to be bought – and were feats of considerable ingenuity. The lens hole and the focus plate had to be accurately aligned and the whole structure made sturdy enough to withstand extreme temperatures, continuous transportation and the constant risk of it being knocked over as it was set up on the narrow pavements of Kabul.

The camera boxes were often brightly painted or decorated with patterns and charms to attract the attention of curious passers-by. As artist Lukas Birk and Sean ethnographer Sean Foley point out in this fascinating book, every single camera was different, and dealing with their idiosyncrasies – leaking light, rickety tripod legs, the long sleeve through which the photographer had to manipulate the negative, sight unseen – was an art in itself. For several generations of Afghan children, the camera remained a thing of magically transformative power.